I Used Major Scale Modes to Write a Song for My Cat

Disclaimer for musicians, both aspiring and accomplished — I am not a trained professional in the field of music. As such, this article should not be interpreted as complete or accurate in terms of music theory. There are already countless sources of accurate information online. My goal is just to share the story of how my understanding of major scale modes helped me to write a song for my cat.

Also, a heads up for cat lovers — this article is also about my cat Jambi, who passed away in June of 2019. As a result, it may get a bit emotional in here.

Backstory

The Band that Started It All

I’ve been playing guitar since around the time I graduated from high school in 2004. In the years leading up to that point, I became friends with some self-proclaimed metalheads who were always sharing new music with me. While it would be some time before I’d learn to appreciate most of it, one band in particular resonated with me almost immediately — Tool.

Something about their style really got my attention. Aside from the subtle use of odd and ever-changing time signatures (my obsession with which will surely be the subject of a future article), the music felt simpler, and yet deeper somehow. It wasn’t until a few years after my discovery of the band that I realized how many Tool tracks are great for new guitarists to learn, and I eventually decided it might be fun to join their ranks.

My First Guitar (well, sort of)

In true Tool fan fashion, I picked up an ebony Epiphone Les Paul, which is effectively the budget version of Adam Jones’ silverburst Gibson Les Paul.

I did briefly own a Fender Squire (link omitted intentionally), but let’s pretend that didn’t happen.

As this article isn’t really about Tool or my guitar, I’ll summarize here by saying that it was only a matter of time before I was able to play the majority of Tool’s discography, and quite well, if I do say so myself!

My Cat

By this time, I was a proper adult and living on my own. What better time to get a cat, right? Enter Jambi, named after the Tool track, and definitely not this guy.

Jambi was a very timid little black cat, the runt of a litter. We first met after a friend informed me that a stray had given birth to a litter under their porch and they all needed homes as soon as possible. While the rest of the kittens were climbing all over the bathroom where the entire family was temporarily housed and cared for, Jambi stayed tucked away behind the toilet, keeping so still that I almost didn’t notice him at all. As a low-key guy myself, and someone who is mindful enough to take special care in making a timid kitten feel as comfortable as possible, I decided we would be a perfect match. 🖤

Bringing It All Together

After about a decade of playing the same old Tool songs and understanding basically none of the music theory, I decided it was time to step things up and learn a little bit of the why behind it all.

I took guitar lessons for about 6 months, explaining right at the start that I needed less help with my playing and more help making sense of basic music theory in a practical way. Over the course of maybe 10 sessions, my instructor helped me understand that what I really needed to be focusing on were major scale modes (referred to simply as “modes” from now on).

Unfortunately, it was around this time that Jambi got sick. Really sick, in the “just make him as comfortable as possible” sort of way. There is nothing good I can say about the situation, but it did give me the motivation to continue learning about music, with a new goal of writing some kind of musical piece to express how I was feeling.

So with that as my focus, I began working to understand modes and some ways to use them as part of a songwriting process.

Major Scale Modes

(As a reminder, please note the disclaimer at the top of this article before continuing beyond this point.)

What Are They?

Modes are a particular type of scale, or series of notes in order of pitch. Each mode, which we’ll look at soon, has unique characteristics that allow it to feel more or less appropriate in different musical contexts (similar to how playing a minor chord generally feels appropriate in the context of a melancholy piece).

My understanding of modes only began to take shape once I recognized two very important facts.

Modes are scales which contain all of the notes in a key, and only those notes.

All modes within a given key contain the exact same notes, and in the same order. The only real difference is where the series begins in the key.

What Aren’t They?

Modes are not the most important aspect of music theory by any stretch. Learning them won’t make you an amazing musician or composer, and there are plenty of good arguments online against learning them at all (outside of very specific situations, such as for academic purposes).

In short, I don’t care. Understanding them has helped me immensely in working toward my goals, and it’s not my place to assume the goals of others.

Why Learn Them?

I became convinced that learning what modes are and how to use them were worthwhile goals for several reasons. Aside from helping me learn to play in key, or even taking context into account in my playing, I found that the unique “shape” of each mode on the fretboard made experimenting with melodies and interesting chords feel far more natural and effortless than anything I’d experienced prior.

To put it another way, reorganizing your living space won’t change the contents of the room (just like switching modes won’t change the notes in the key), and yet the new arrangement naturally feels different and the way you play and write in that new context can easily result in a change in comfort and creativity, depending on what is being played.

Needless to say, this is far from the most important thing to know about modes, but it seems to be the most important to me when it comes to actually playing guitar.

Taking a Closer Look

Because the details of each mode have been covered so well in other places, I won’t attempt to duplicate that work entirely. Instead, I will reference the images below, which I’ve adapted from this source image. I chose this image because it represents scale patterns where exactly three notes are used on each string, which people seem to prefer for learning purposes.

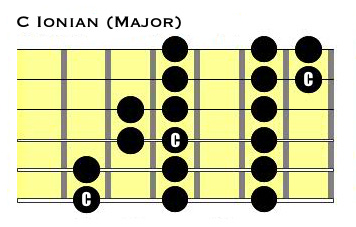

To start, let’s take a look at the Ionian mode in the C Major scale.

In the image above, all of the notes in the key of C Major (C, D, E, F, G, A, and B) are marked with black circles, and the root (first note) of the mode (not the key) is labeled. As Ionian is the first major scale mode, the root note and the key happen to be the same.

Tip: Try to focus on the simple facts above and don’t worry about what it all means just yet. These are just patterns of notes on the fretboard which cover the entire key.

Let’s take a look at another mode and then we’ll compare the two and identify some differences worth noting.

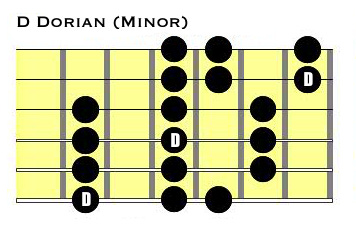

Now let’s look at the Dorian mode, again in the C Major scale.

Just like with the first image, all of the notes in C Major are marked with black circles, and the root of the mode is labeled. As Ionian was the first mode and began with the first note in the key (C), Dorian is the second mode and so it begins with the second note in the key (D).

Fundamentally, the only thing that’s changed from the Ionian mode is our position on the fretboard. All of the notes are the same, but the pattern they form on this segment of the fretboard differs because of where the notes in the key happen to fall in relation to one another.

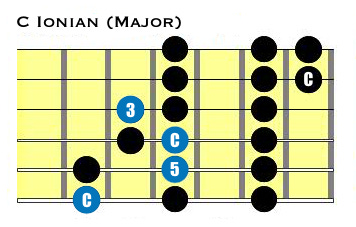

To illustrate the point above, look at each of the two previous images and consider which basic chords can be constructed using only notes marked with black circles. In the Ionian mode image, for example, you’ll find that the common major chord shape (marked in blue in the image below) is possible from the root of the mode. Can the same chord be formed from the root of the Dorian mode? If not, which chords can be formed?

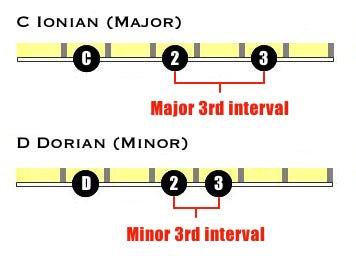

You should be able to see that the Dorian mode does not contain the note at the major third interval from the root (D), but it does contain the minor third. This makes it possible to form a common minor chord shape using only the notes marked with black circles in the Dorian mode image.

To summarize the conclusion we reached above, Ionian is a major scale, in that the third interval (distance between the 2nd and 3rd scale degrees) from the root note is a major interval, whereas Dorian is a minor scale, in that the third interval from the root note is a minor interval. This is illustrated in the image below.

Exploring the Remaining Modes

In the previous section, we looked at two modes (Ionian and Dorian). While we saw that they contained exactly the same notes, due to being in the same key, we also identified how the difference in intervals resulted in different possible chords within the mode. For the same reason, it should now make sense why different modes have different characteristics (such as being “major” or “minor”) even though they contain the same notes.

These same ideas extend to the remaining modes, and I will quickly cover them in this section.

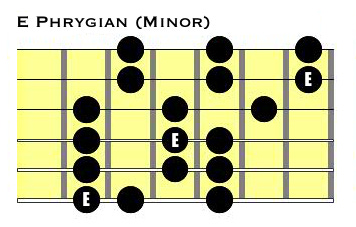

The third mode is called Phrygian.

Similarly to the Dorian mode, it is a minor scale.

Note: If needed, revisit the previous section and pay close attention to what makes Dorian a minor scale. You should find that the same is true for the Phrygian mode.

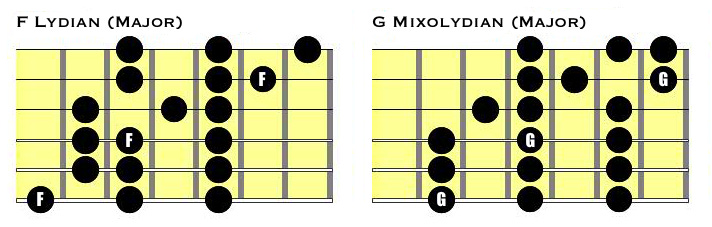

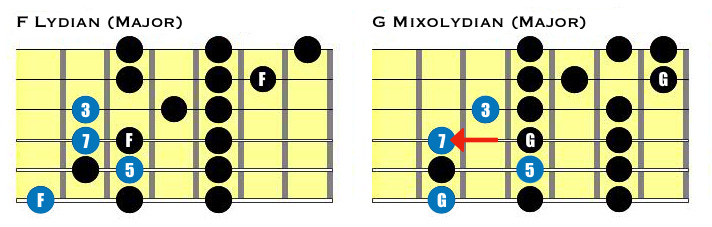

The fourth and fifth modes are called Lydian and Mixolydian, respectively.

Both Lydian and Mixolydian are major scales, but they differ in several ways. For example, consider a major 7th chord from the root note of Lydian (F). It wouldn’t be possible from the root note of Mixolydian (G), though you could flatten the 7th note, resulting in a dominant 7th chord instead. See below for an illustration of this difference.

If you’re familiar with a variety of other chords, you may be able to spot them in these patterns as well.

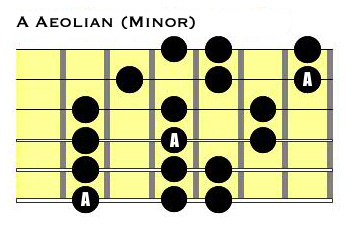

The sixth mode is called Aeolian.

At this point, it should be easy to tell that this is a minor scale.

Note: As is true of all of the modes, there is plenty more to say about this mode, however most additional information is well outside the scope of this article.

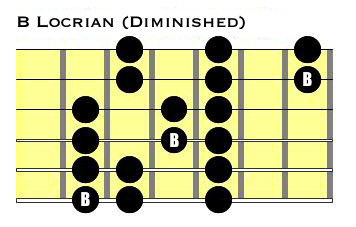

The seventh (and final) mode is Locrian.

While technically a minor scale, Locrian is often referred to as a diminished scale, specifically because it contains a flattened fifth scale degree. As a result, chords in this mode tend to be more dissonant and less conventionally pleasing to the ear. Can you see the diminished fifth in the mode diagram above?

Wrapping Up Modes

Before we continue to the song I wrote for my cat, let’s quickly recap some of the main points that I find useful to understand about modes.

All modes in a key contain the exact same notes (or else they wouldn’t be in the same key).

Each mode has a unique root note, which causes the intervals between the root of the mode and any given note in the scale to differ from one mode to the next.

Within the context of each mode, different chords can be formed, and common chords can be modified in interesting ways.

Because of the difference in layout of the notes from one mode to the next, simply playing in a different mode often changes the playing style and, thus, the feel of the piece being played.

Knowing the properties of different modes can make it easier to compose or even improvise music when information about the context is known. For example, need a minor chord? Look to Dorian, Phrygian, and Aeolian modes!

Jambi

In the previous section, we covered a lot of basic information about major scale modes, including some common patterns for playing guitar within the context of each.

Hopefully, I have made it easy to see how becoming comfortable with the various patterns and how they sound allows a guitarist to move more freely around the neck of the guitar, and more easily discover interesting chords and new melodies.

In this section, we’ll take a look at a song which I wrote for my cat, Jambi. It was composed entirely by experimenting with different modes to find just the right melodies, chords, riffs, and so on.

Please keep in mind that this was the first song I ever wrote. I really think that fact speaks to the utility of modes when composing music.

Applying Modes to Measures

The video below covers the first verse and chorus of “Jambi”.

Tabs are displayed in the top 2/3rds of the clip, and the bottom 1/3rd shows the notes played in real time on a guitar neck.

The bottom-left corner of the video displays the name of the mode that I was experimenting with when I wrote each piece being played. You should be able to cross-reference the notes in the video with the mode pattern images used earlier in this article.

Also, remember that the modes are just a guide, like anything else in music. You can technically play any note at any time, so I do get a little creative here and there!

Note: The patterns which can be used for each mode do not change between keys, so although this track is written in the key of A Major (as opposed to C Major which we worked with earlier), that shouldn’t cause any confusion.

Also, it’s been suggested that I should’ve written the song in the key of B, and titled it “Jam B”. While clever, I ultimately went with the key that felt right to me.

Extra credit: In the video above, there are 2 distinct notes used which are out of key. Can you spot them? 🔎

Modes can be used to change the feel of a piece of music as it progresses, with the idea being that if you’re playing in B Dorian, for example, the emphasis of the melody should be on the B note itself, and variations of B Minor chords.

However, my goal here is to demonstrate that the different mode patterns, as they appear on the guitar neck itself, helped me to be more creative in how each measure was written and played.

To drive this point home one last time, consider a simple melody which can be played across three strings on the guitar. In most cases, this exact series of notes can be played in multiple places on the guitar neck. Imagine the difference between playing this melody in a way that involves the 2nd string (the B string, in standard 6-string tuning), compared to higher up the neck where the 2nd string is not involved. The position of the notes relative to one another will have changed due to the way the 2nd string is tuned relative to the 3rd string (a difference of 4 semitones, rather than 5 as found in every other case).

That’s it! I hope at least some of this mess of an article made sense and that it will help you write something you enjoy!